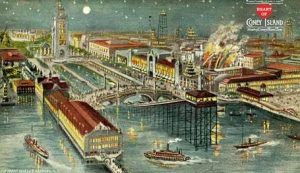

Coney Island today has undergone a wonderful revival with its colorful Mermaid Parade, exquisitely refurbished Wonder Wheel and Steeplechase rides—all of which harkens back to its glory days. At the turn of the last century, Coney Island was a major seaside resort that drew hundreds of thousands of well-heeled visitors daily to its many rides and sideshows. In its heyday, there were three amusement parks—Luna Park, Dreamland and Steeplechase Park. Visitors could ride in gondolas through a miniature Venice; witness the fiery eruption of Pompeii or travel undersea to visit the famed and mythological Atlantis. They could also venture into the novel and bizarre sideshows featuring human torpedoes, sword swallowers and babies in incubators.

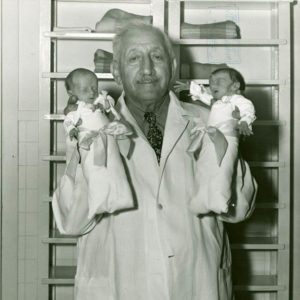

In 1903, Martin Couney better known as “the incubator doctor” garnered the wrath of the American medical establishment over his exhibit of premature babies. In Europe, incubators were an accepted practice. France, which pioneered and adopted incubators, was the leader. However, many American doctors still held the view that premature babies were genetically inferior weaklings and untreatable. Without intervention, the majority of these infants were likely to die.

However, Couney became their unlikely champion. He was the father of a premature baby and was dedicated to her survival as well to the other children that came his way. In terms of stellar credentials—he had none. There is no proof he was a doctor or even French, as he had once claimed. Neither was he a professor at a great university nor a surgeon at a teaching hospital with a following. He might possibly have been a German-Jewish immigrant who studied medicine or sold surgical instruments—whatever he was—he was condemned by many as a promoter and a quack.

Nevertheless, he was determined to prove his adversaries wrong. He operated a spotlessly clean hospital-like facility and employed skilled nurses and physicians to monitor and care for the babies. According to records, “each incubator was more than 5ft (1.5m) tall, made of steel and glass, and stood on legs. A water boiler on the outside supplied hot water to a pipe running underneath a bed of fine mesh on which the baby slept, while a thermostat regulated the temperature. Another pipe carried fresh air from outside the building into the incubator, first passing through absorbent wool suspended in antiseptic or medicated water, then through dry wool, to filter out impurities. A chimney-like device with a revolving fan blew the exhausted air upwards and out of the incubators.” Many of the preemies came from local maternity wards which couldn’t or wouldn’t take care of them. Couney on the other hand, gladly accepted babies of all races and backgrounds. To him, they were all worth saving.

In 1903, it cost about $15 a day ($405 or £277 today) to care for each baby, which was considered expensive at the time. Knowing the parents couldn’t afford the costs, Couney had the public pay an admission fee. The public, intrigued by these underweight and undervalued tots, came in droves. This allowed Couney to cover his operating costs, pay his staff good wages and use the profits to plan more exhibits. His Coney Island incubator exhibits ran from 1903 through the 1940s and expanded to other fairs and expositions creating interest in these life-saving incubators.

His relationship with famed American pediatrician, Julian Hess, who became known as the “Father of American Neonatology” brought Couney credibility and gravitas. Together they

operated incubators at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago. But it took roughly 36 years after his exhibits for the establishment of a hospital ward dedicated to the care of premature babies at a New York hospital in 1939. (That hospital is believed to be NYP/Cornell-Weill Hospital today)

Whether you believe he was a showman or charlatan, he changed the way preemies were treated, no doubt saving thousands of lives in the process (6,500 by Couney’s own account). He was also a staunch advocate for breast milk and meticulous about hygiene—a man well ahead of his time.

Which makes me wonder— could a man or woman with enough passion find a cure for a disease or medical condition without a university degree and without years of clinical trials today? Let’s hope Martin Couney’s story continues to inspire others who may think that because they don’t have the “proper credentials” they can’t make a difference.

Read more about Martin Couney in these BBC and Smithsonian articles.

Strategic Communications Professional/Content Strategist/Marketing Communications Consultant